Investigadores de la Universidad de Turku en Finlandia encontraron que el eje de rotación de un[{” attribute=””>black hole in a binary system is tilted more than 40 degrees relative to the axis of stellar orbit. The finding challenges current theoretical models of black hole formation.

The observation by the researchers from Tuorla Observatory in Finland is the first reliable measurement that shows a large difference between the axis of rotation of a black hole and the axis of a binary system orbit. The difference between the axes measured by the researchers in a binary star system called MAXI J1820+070 was more than 40 degrees.

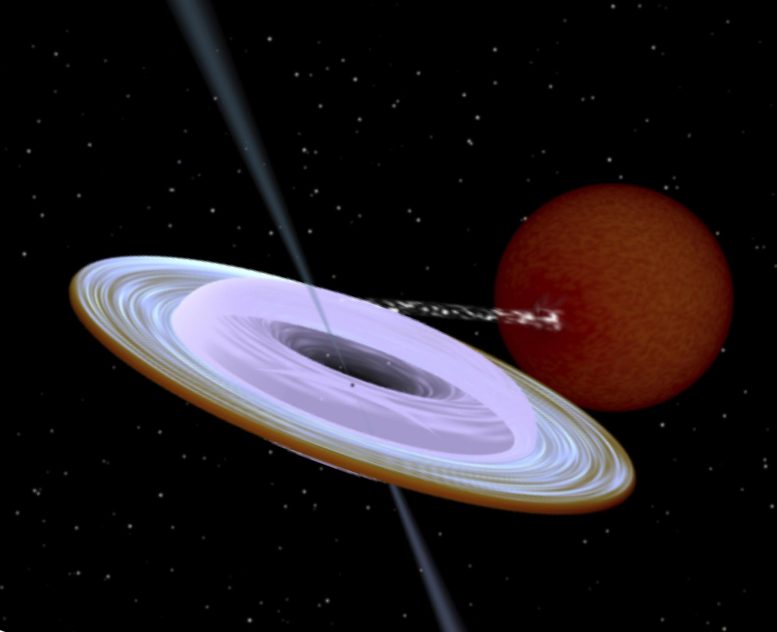

Artist impression of the X-ray binary system MAXI J1820+070 containing a black hole (small black dot at the center of the gaseous disk) and a companion star. A narrow jet is directed along the black hole spin axis, which is strongly misaligned from the rotation axis of the orbit. Image produced with Binsim. Credit: R. Hynes

Often for the space systems with smaller objects orbiting around the central massive body, the own rotation axis of this body is to a high degree aligned with the rotation axis of its satellites. This is true also for our solar system: the planets orbit around the Sun in a plane, which roughly coincides with the equatorial plane of the Sun. The inclination of the Sun rotation axis with respect to orbital axis of the Earth is only seven degrees.

“The expectation of alignment, to a large degree, does not hold for the bizarre objects such as black hole X-ray binaries. The black holes in these systems were formed as a result of a cosmic cataclysm – the collapse of a massive star. Now we see the black hole dragging matter from the nearby, lighter companion star orbiting around it. We see bright optical and X-ray radiation as the last sigh of the infalling material, and also radio emission from the relativistic jets expelled from the system,” says Juri Poutanen, Professor of Astronomy at the University of Turku and the lead author of the publication.

Impresión artística del sistema binario de rayos X MAXI J1820 + 070 que contiene un agujero negro (un pequeño punto negro en el centro del disco gaseoso) y una estrella compañera. Un chorro estrecho se dirige a lo largo del eje de rotación del agujero negro, que está fuertemente sesgado con respecto al eje de rotación de la órbita. La imagen fue producida con una brisa. Crédito: R. Hynes

Al seguir estos chorros, los investigadores pudieron determinar con mucha precisión la dirección del eje de rotación del agujero negro. Cuando la cantidad de gas que caía de la estrella compañera al agujero negro comenzó a disminuir, la temperatura del sistema se enfrió y una gran parte de la luz del sistema provenía de la estrella compañera. De esta forma, los investigadores pudieron medir la inclinación de la órbita mediante técnicas espectroscópicas, y esta coincidió aproximadamente con la inclinación de la balística.

“Para determinar la orientación 3D de la órbita, también se necesita saber el ángulo de posición del sistema en el cielo, lo que significa cómo gira el sistema con respecto a la dirección norte en el cielo. Esto se midió usando técnicas de polarimetría”, dice. Juri Potanin.

Los resultados publicados en Science abren interesantes perspectivas hacia los estudios de formación de agujeros negros y evolución de estos sistemas, ya que tal desequilibrio extremo es difícil de obtener en muchos escenarios de formación de agujeros negros y evolución binaria.

La diferencia de más de 40 grados entre el eje orbital y la rotación del agujero negro fue completamente inesperada. Los científicos supusieron a menudo que esta diferencia era muy pequeña cuando modelaron el comportamiento de la materia en un espacio-tiempo curvo alrededor de un agujero negro. Los modelos existentes ya son complejos, y ahora los nuevos hallazgos nos obligan a agregarles una nueva dimensión”, dice Potanin.

Referencia: “Desequilibrio de rotación de agujero negro órbita-órbita en binario de rayos X MAXI J1820+070” por Guri Potanin, Alexandra Veledina, Andrei V Berdyugina, Svetlana V Berdyugina, Helen Germak, Peter J. Juncker, Gary JE Kagava, Ilya Kozenkov, Vadim Kravtsov Filippo Perola, Manisha Shrestha, Manuel A. Pérez-Torres y Serge S. Tsygankov, 24 de febrero de 2022 Disponible aquí. saber.

DOI: 10.1126 / ciencia.abl4679

El principal resultado se obtuvo utilizando el polarímetro DIPol-UF construido internamente e instalado en el Northern Optical Telescope, propiedad conjunta de la Universidad de Turku con Universidad de Aarhus en Dinamarca.